Burghers, dim sum, and... Chapter 2

- Hans Ebert

- Sep 17, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 25, 2021

The feeling of arriving in Hong Kong was pretty much indescribable. I was nine years old and had never seen so many Chinese people in one place. It was stranger in a strange land stuff- but stranger.

We were met by my Auntie Prim, her husband Gus Da Rocha, and my father’s younger brother Uncle George. He had left Ceylon a couple of years earlier and had settled into life in Hong Kong.

It was then into a taxi and we were on our way through neon lit streets, past rickshaws and trams to what would be my family’s home for about two years- a tiny apartment in North Point and on the 27th floor of Fung Wah Mansion.

It was hardly a “mansion” whereas neither myself nor my mum and dad had ever been in an elevator.

It was quite a trip with my mother’s fear of heights taking over her entire being and she insisting walking up twenty seven flights of stairs.

As for the “mansion”, it’s where Burgher Family Ebert, the Da Rochas and a highly strung French poodle somehow managed to co-exist and make things work for us.

Auntie Prim was a wonderfully kind lady. She and her younger sister Rica were meant to have been absolutely stunning in their youth when living in Colombo. They still were.

Having seen old photos of them, they really had those old Hollywood movie star looks not unlike actress Joan Crawford.

Auntie Prim was a music teacher and gave piano lessons after work. She was very proper and her annual parties for her piano students which were held in the tiny apartment where we all lived were extremely fastidiously arranged events.

She did so much for everyone in the family and it was good that she eventually settled down in Sydney, happy being with Suzanne and her Australian husband Ken. Ken was a top man.

The night we arrived in Hong Kong was the first time I met my cousin Suzanne, who was blonde and the same age as me. We looked a little different from each other.

Did we realise this? No. Kids don’t categorise. Well, most don’t. The categorising comes from the parents.

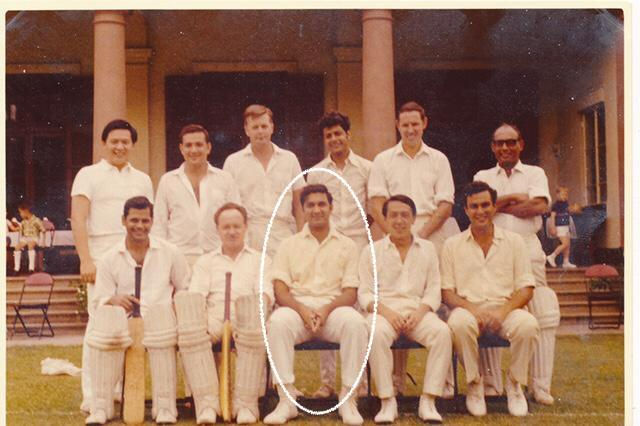

I also met the Ebert family matriarch and my grandmother Hilda, my Auntie Rica, who was a physiotherapist, and her two sons Carl and Tony Myatt, both older than me and very good cricketers. Uncle George lived with the Myatts.

That first night in Hong Kong, I was also introduced to cutlery and learned how to feed myself by watching how my cousin used her spoon and fork.

My grandmother, who was an excellent cook, had prepared a mild curry and rice. After

finishing my meal and feeling very proud with myself for cleaning the plate clean, Uncle Gus mentioned that it was rude to almost lick the plate dry. Jeez, I missed my Podi feeding me. I didn’t however feel I would miss Ceylon.

I was accepted and attended the same primary school as Suzanne. It meant taking a tram from North Point to Shaukiwan, crossing the road and walking up and down over 350 steps to reach Quarry Bay Junior School.

I didn’t realise that I was the only coloured kid at Quarry Bay and what people thought about me having a blonde cousin. I hadn’t noticed the difference. Kids don’t think of these things.

This difference only hit home when a bigger German kid kept taunting me every lunch break by calling me the ‘n’ word.

This, I didn’t understand. I cried to dad that I was brown, so why was I being described being black.

I daubed myself with a little talcum powder on my face every morning to look more “fair”, but I got tired of that.

I survived the name calling and made friends with a few kids like Timothy Hall, an extremely smart Eurasian who went onto be a finalist for the prestigious Booker Prize as Timothy Mo and his semi autobiographical book “Sour Sweet”. He left Hong Kong when 10.

I met him some years later in London when his career as a writer was starting to take off. I remember him persuading me to buy a black velveteen jacket for an astronomical price. I don’t think I saw him again in London.

He was a little hyper and I still remember him asking if anyone in the UK had referred to me as being a “wog”. Strange guy.

We met several years later in Hong Kong. I don’t think he was expecting me to be with a woman and was no longer the shy kid he knew. It seemed to make him uncomfortable.

He made a hasty exit mid sentence and there was no more Mo. Stranger guy than whom I had met in London.

At Quarry Bay, there were also a couple of very pretty girls in school and things were good.

Though I didn’t know him well, I remember the day Bobby Samarcq’s father- gentleman jockey and champion Hong Kong Jockey Marcel Samarcq- died when falling off his horse and the races at Happy Valley that Saturday afternoon being abandoned.

I was good at spelling, I represented Quarry Bay in inter-school poetry reading competitions, was good at arithmetic, art, good in especially relay races and playing rounders. Rounders. I know, I know.

I was given the role of the character Black Thunder Cloud in the major school play of the year and was a success in it.

The dampener was being told by the same racist bully who tormented me every lunch time that the only reason I was given the role was because- you guessed it- I was black.

By now, however, I was confident in myself and no longer the lonely kid I was in Ceylon.

The teachers including the headmistress liked me though to some classmates I probably came across as a bit of a creepy teachers pet. I couldn’t help it. It was exactly what I wanted to be.

As school was only half day, mum had arranged for me to have lunch at a restaurant close to where we stayed. It was a typical Chinese restaurant that had a few Western dishes.

I absolutely loved the way they made their Beef Curry Rice- it was some local curry paste mixed with sautéed pieces of beef and potatoes, but I loved the taste.

The waiters and cook would come out to watch me eat. I never knew why. My colour? For dessert, I always had their jam pancakes, something I had never tasted before.

Meanwhile, my parents were looking for jobs. Mum found one as a secretary for a chartered accountants firm and dad joined a small travel agency in Sales. He was the only salesman.

When not watching Cantonese dramas and black and white television shows, Suzanne and I got together and made up games like jumping down from one flight of stairs to the other. It’s a wonder we didn’t suffer some serious injuries.

At school, however, there was a bit of jealousy taking place as Suzanne had trouble keeping up with the resident nerd- me. I was promoted one year and she wasn’t.

This saw her change schools as apart from our levels of academic differences, discussed by many was the difference in our colour despite supposedly being related.

It was awkward for everyone- that is until Suzanne was told the truth when she was 16- how she was French, had been abandoned by her mother and was adopted by my aunt and uncle. This explained much.

My family and I eventually moved to another apartment in Fung Wah Mansions- actually a room- which belonged to an old female doctor. It was a depressing place to stay. Awful. But it was cheap. And when I got chicken pox, at least there was a doctor in the house.

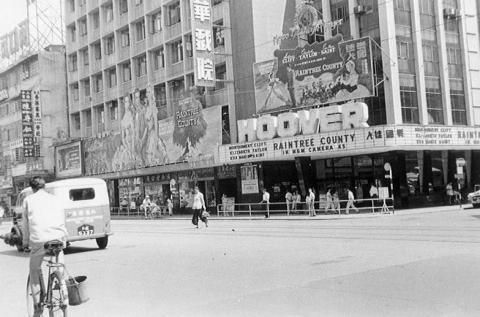

We moved out of this building and to another tiny flat across the road and next to what was the Hoover Theatre.

When not playing with my new best Portuguese friend from school named Jose, my favourite game was sitting by the window, looking at the traffic below and taking down the number of car number plates. Why? Why not?

The rest of the time, I would pretend to be different cricketers and play in front of a cupboard mirror in our one bedroom with a beat up old bat I had brought with me from Ceylon.

Even with a phone outside and shared by others on the same floor, this flat was more spacious than living in a shoebox with the rest of the Ebert and Da Rocha clan.

If there was a highlight to my days other than selling my dad’s classic record collection so I could buy old issues of Playboy and Penthouse and discovering the rudiments of sex, it was pretending to be a disc jockey and creating my own radio show.

It was this or waiting for mum to come home after office every Saturday lunch time with a $1.80 box lunch for me from Hong Lok Yuen. The Baked Pork Chop with Rice was a favourite.

We were poor, but happy. At least I was. Who knew what were my parents thinking? I don’t believe my mother was ever happy.

Meanwhile, I was getting ready to attend the Secondary School that was KGV. This was going to change everything. Everything

Comments